Talking To Ealing's Homeless People

A visit to the soup kitchen at St. John's Church

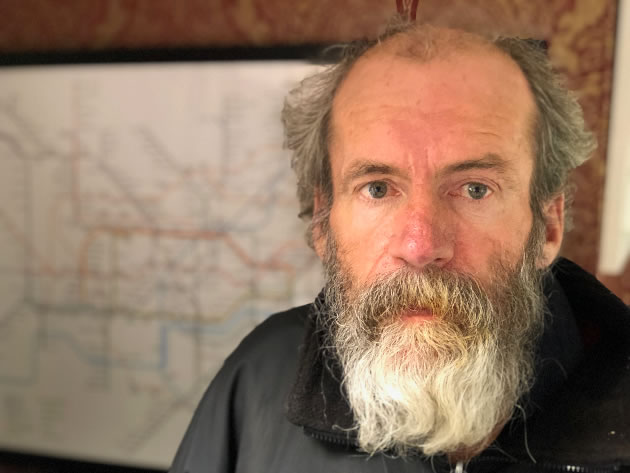

Niall O'Connor

“People generally talk about them – not to them.”

Andrew Mcleay is talking about the homeless. With the soup kitchen he runs at St John’s Church in West Ealing in full swing, there are plenty of homeless people around to talk to.

As some rifle through the free clothes on offer, others are taking the chance to grab a quick shower. Some, who aren’t homeless at all, are just enjoying a cup of tea and a chat. The last group are part of a changing demographic of the needy.

Some are housed or own cars, and are often in some form of work or recently laid off. But they attend soup kitchens and food banks just for some company. Or they are living on the breadline and in need of a free meal.

Among them, sitting quietly on his own, reading the paper, is Niall O’Connor.

With a copper-grey beard working its way out of control, he could be the very personification of homelessness. That is, until you speak to him. Niall, now 55, says he has been homeless intermittently since his mid-20s, and has spent the last four years on the street.

He said: “I’ve been around for a long time, around the soup kitchens and around this church as well.

“You know, I’ve read a lot of homeless people is a result of relationship problems.”

That certainly led to his most recent bout of sleeping rough, when four years ago he fell out with the parent who was housing him.

He says it has reached the point that he no longer bothers with social housing lists. That would take too long, and he says he’s deemed almost un-housable

“You always think of being housed securely as being preferable, but as I say, I’m quite content at the moment. I’m more used to it,” he says.

If there’s one thing Niall says he would like people to understand, it’s the loneliness.

It’s a sentiment shared by George, who asked that we only use his first name to avoid appearing on Google searches.

George

George was last homeless in the late-80s, and the experience has kept him in the voluntary sector ever since.

Taking a break from his shift at the soup kitchen, he remembers how, after breaking off contact with his family, he didn’t talk to anyone for about three months. Despite being in one of the most populated cities on the planet, he might as well have been a hermit.

He remembers: “A well-known character called Charlie was one of the first people to speak to me. I was sitting on a park bench and he was a great help to me, but he was what they would call in the old days a tramp.

“It was therapeutic, just talking.”

George said over the last 20 years life has become harder for those at the bottom, and the demographic at the soup kitchen had changed. Many of the clients these days are eastern Europeans who have come over to work, but been undercut by even cheaper labour from elsewhere.

He said: “There’s a lot more problems with housing and drug taking than there was then.

“We deal with people who have got problems with loneliness, not fitting in, some of them have got houses, some of them drive cars.”

In George and Niall’s cases, homelessness was a direct result of a sudden breakdown in family relationships.

Mary

Mary also found herself homeless, but this time it was after police raided her accommodation. She is unwilling to talk much about her past, but says for women, the streets hold whole new threats.

“The first night I slept out was the coldest night of the year. It was a long time ago but I’ll never forget it,” she says.

She says for many, she has become something of a mentor, offering advice from how to hide your money with a safety pin inside your clothes, to the best way to get back into accommodation.

Now back in accommodation, she volunteers at soup kitchens, saying she has something like a sixth sense for how to deal with those suffering drug and alcohol addiction.

Andrew McLeay who runs the soup kitchen

Andrew Mcleay, the man running the soup kitchen, also has a special insight to the struggles of his clients. Despite arriving from Australia with a decent amount of savings, a lack of available accommodation saw him spending £900 a month on a flat, and before long he was almost destitute.

He says the reality of London, with its expensive rents and falling government spending on social security, can mean even the prepared find themselves on the streets. The demand on his soup kitchen, he says, has escalated as a result. His statement is backed up by figures from Ealing Foodbank suggesting demand for food parcels has more than doubled in a year in parts of West London. Ealing residents needed 11,546 emergency three-day food parcels in the year to March – that’s more than double the 5,624 parcels handed out the year before.

Hillingdon’s demand had also skyrocketed, from 2,203 in 2017-2018 to 4,510 in the year just gone.

Nationally, 1.6 million food parcels were given out according to the Trussel Trust – a 19% increase on the previous year. In both London boroughs, about a third of the emergency food parcels went to children.

With Andrew estimating 10% of the 400-odd people who use his soup kitchen being either in work or recently out of work, it’s no surprise the demand is going up when the slip into destitution can happen so quickly.

For more information about Ealing Food Bank, visit their web site.

Ged Cann - Local Democracy Reporter

May 29, 2019

Related links

|